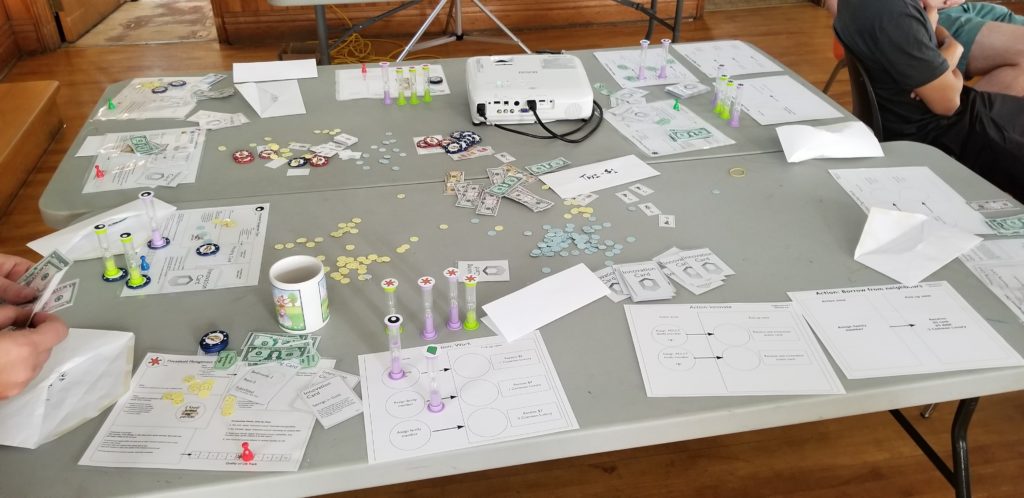

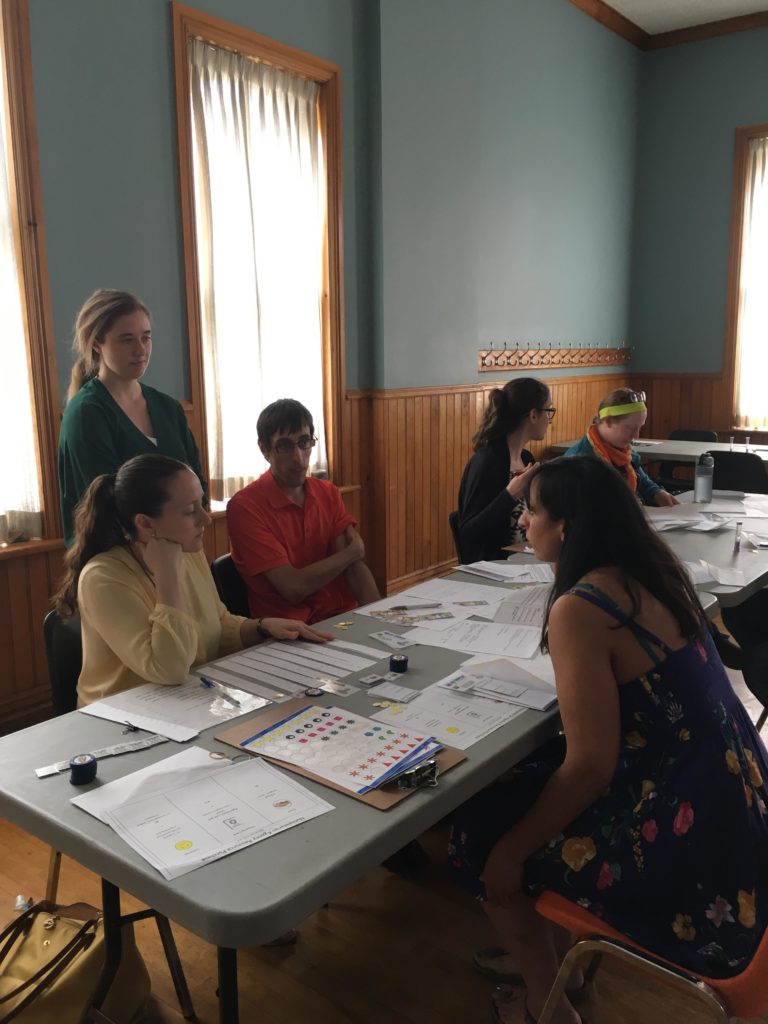

In preparation for our July 6/7 simulation-based course, “The Day My Life Froze”: Urban Refugees in the Humanitarian System, LLST organized an invite-only test-run of the simulation here in Ottawa on June 22nd.

Invitees included displaced people, local NGOs, government agencies, and others with an interest in the subject matter. We arranged the test as we had made significant additions to the simulation mechanics since the last test run. These included:

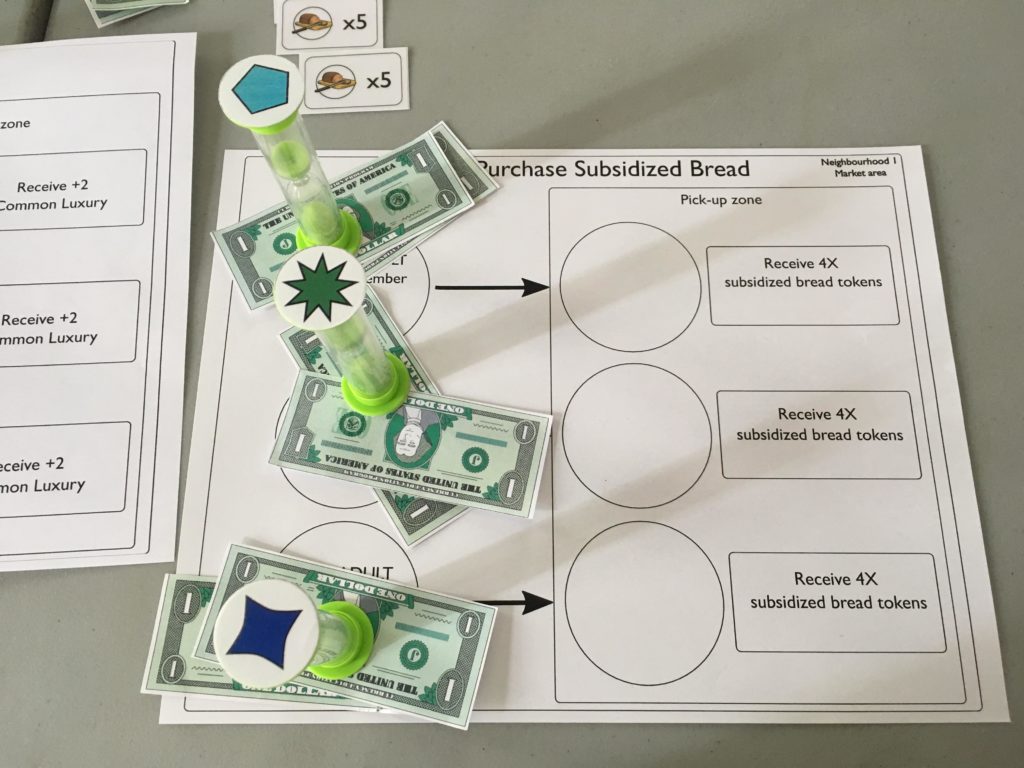

- An increased range of options for humanitarian actors to provide support for displaced households, including more flexibility in what aid can be supplied and when.

- More detailed project cycle for humanitarian workers, including project proposal templates and a donor-driven revision process.

- An addition of three more displaced households, and additional opportunities for these households to gain income.

- Expanded donor responsibilities (which we can’t really tell you about without spoiling things, but trust us, they are interesting).

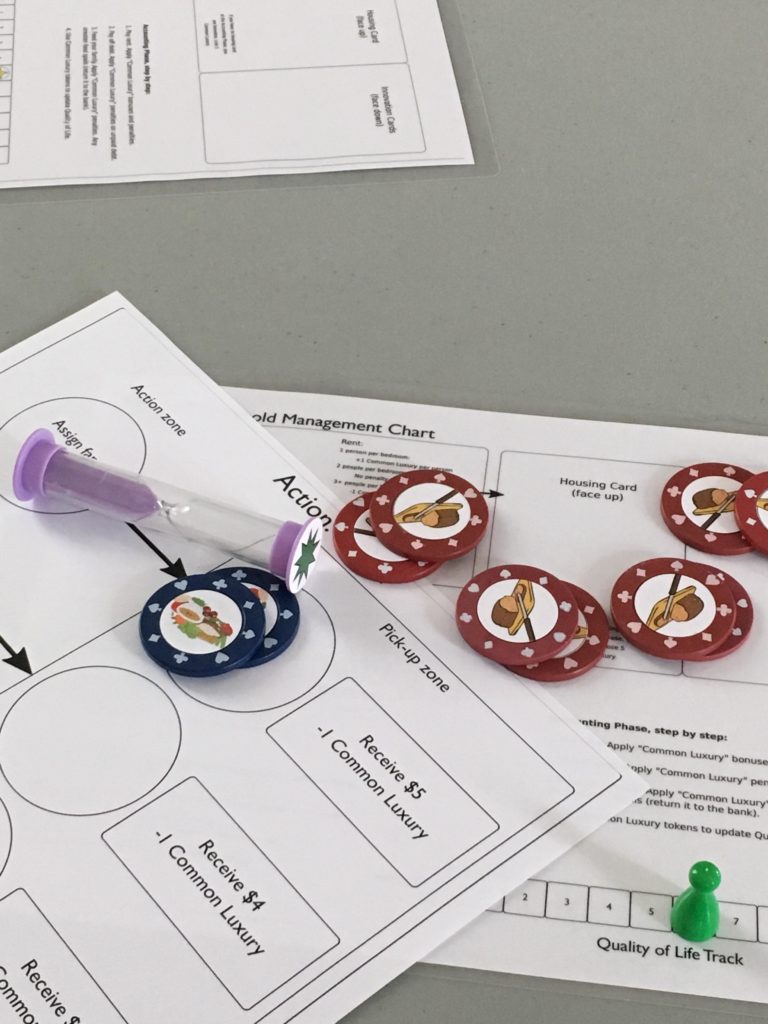

- Various tweaks on the household economies.

The goals of the test were:

- To train our team of facilitators on the updated mechanics, and to orient new facilitators to the simulation in general.

- To stress-test updated mechanics.

- To receive feedback and development suggestions from a community of participants who are experienced in simulations and serious games.

We were happy to find that the changes to the simulation overall worked very well. As in previous runs of the simulation, participants were still engaged and learning–the new elements communicated the additional lessons we had intended. Despite being a serious and respectful exercise, the simulation can be very exciting for participants to explore; participants reported being very absorbed in the simulated world and the challenges they struggled to overcome. As one participant reported: “I really enjoyed the gameplay, even though it was ‘confusing’, ‘frustrating’ and a bit ‘stressful’. But that’s exactly what I’d say it should have been – to give the players a just a little taste of what some refugees experience.”

Some key takeaways included:

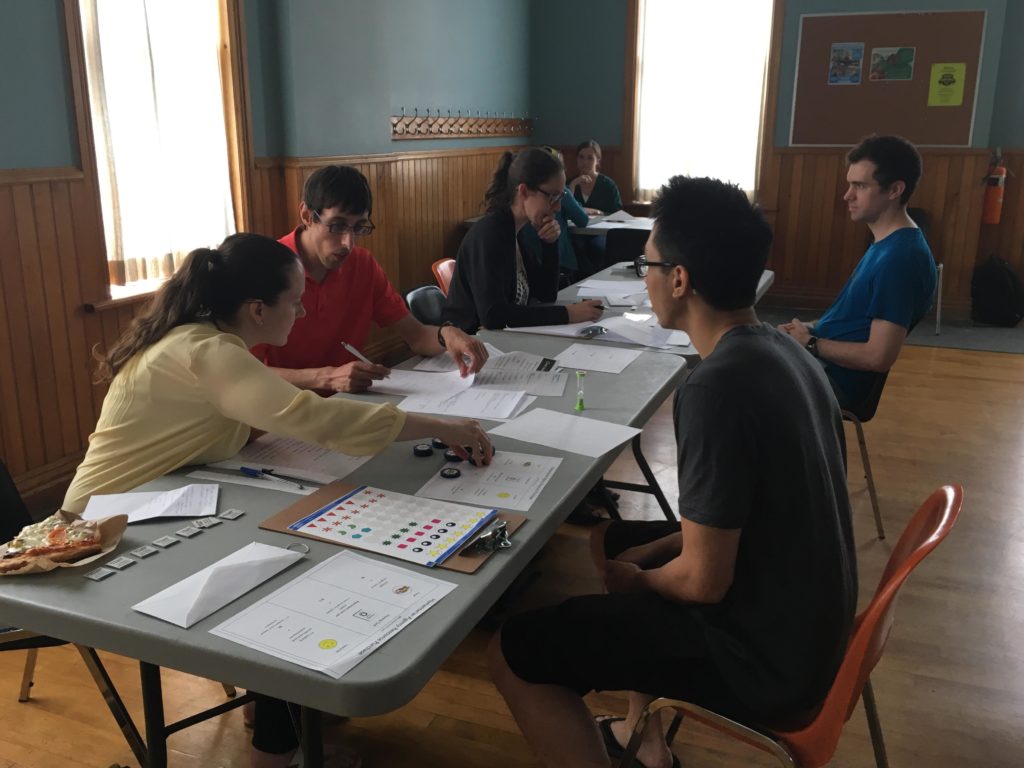

- The use of sand timers communicates the stress of time management and gives a visceral feeling of there “never being enough”. In this run, we had halved the length of time the sand timers would run for, making a much more busy experience.

- The new humanitarian mechanics added considerable stress to the experience; in teams, humanitarian workers had to process data and prepare project proposals to request funding from donors. The interplay between the donor and humanitarians was dynamic and modeled some of the challenges in grant applications and reporting.

- With extra leeway, the humanitarian team came up with innovative interventions, including a cash-for-work program. This was a great representation of humanitarian workers listening to the community and giving what they needed. However, in implementing a cash-for-work program, the humanitarian teams would likely experience push-back from the local host government–something we discussed in the debrief.

There were definitely some fun new challenges we came across:

- A lack of clarity in the humanitarian agency rules led to their receiving more funding than intended. The INGOs were quite pleased with themselves as they were in fact much more economically influential than their real-life counterparts. Unfortunately, this was not very representative!

- The new donor rules, an expanded economy, and our experienced player-base lead to some imbalances in household economics. While these were corrected “on the fly”, we did have a cash-flow problem at the midpoint of the run when it was discovered that some households were hoarding small bills. While this was actually an amusingly succinct representation of cash flow challenges experienced by some states (as anyone who has taken a taxi in Egypt can attest), it was not exactly on our list of teaching objectives.

- While the humanitarian agencies enjoyed the updated project proposal process, they found the new reporting requirements to be much less clear. We will have to develop a few templates to help facilitate the process.

Some exciting things to work on before our course!

See below for a few more images from the playtest.