In early July, the Lessons Learned team presented the latest iteration of our introductory course, “The Day My Life Froze”: Urban Refugees in the Humanitarian System.

Sixteen participants joined us at the Laurentian Leadership Centre from Ottawa, Toronto, and Montreal, including humanitarian workers, government staff, journalists, “group of five” sponsors, and others. This diverse crowd made for rich conversation from which we were all able to learn. It was an honour to get to know them over a weekend.

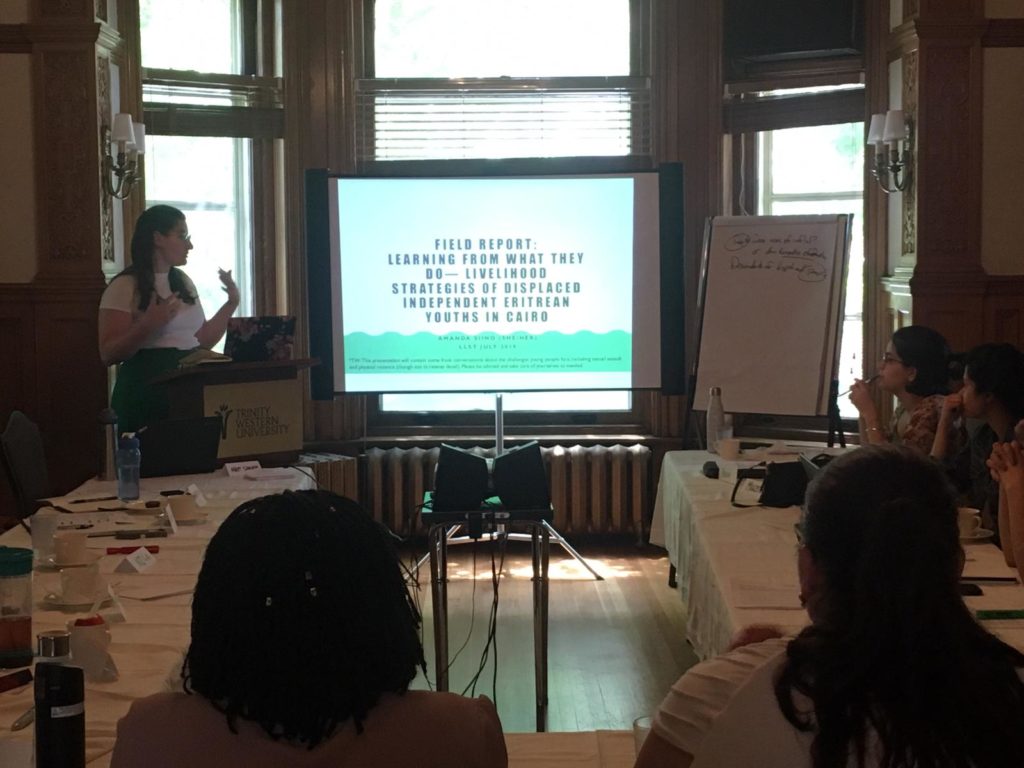

We were able to bring together an exciting group of guest presenters.

Muzna Duried, a Syrian woman and asylum claimant in Canada, presented an overview of the “lived experience” in Syria during the conflict, and a “fact or fiction” exercise about asylum claimants and the Canadian refugee resettlement system. Muzna is an incredible speaker, as well as a Liason Officer for the White Helmets, the founder and coordinator of the “Women Refugees, not Captives” campaign, and winner of the 2019 Canadian Excellence in Global Women and Children’s Health Award (Youth Category) the Canadian Association of Refugee Lawyers Annual Award–to name only a few of the many programs she is involved with! The whole team was excited to have her take part. Her presentation was both emotionally powerful and full of important information. Several of the participants, including the other presenters, were moved by the personal and analytical contrast that Muzna succinctly shared.

Amanda Siino brought a fresh, but jarring case study from her recent research with Eritrean youth living in Cairo, Egypt. The arbitrary ways in which humanitarian aid shifts when a “beneficiary” reaches age 18 upends traditional expectations of vulnerability and acts counter to the goals of humanitarian programming in Egypt.

Bringing a wide range of voices to “The Day My Life Froze” is an important part of ensuring the course is up-to-the-minute and uniquely relevant to each new group of participants.

Johanna Reynolds (part of the LLST team) shared a new, moving session on positionality and privilege among humanitarian workers, including exercises and time for personal reflection. This session was a new addition to the course, and was one of the participants’ favourites. In small groups, we were able to share personal experiences on how “international expats” interact (or fail to do so) with the communities in which we lived.

Matthew Stevens coached participants through an exploration of the goals and motivations of four groups of major stakeholders in any crisis, while brainstorming other communities and sub-groups that might also be involved. Together, we then completed several “red teaming” exercises on inclusivity and perspective, and discussed how these could be applied to and situated within the humanitarian project cycle.

The simulation itself took place on the second day. The unique layout of the Laurentian Leadership Centre allowed us to take full advantage of the spatial elements of the simulation. While donors received humanitarian applicants in the grand sitting room, displaced households struggled to make ends meet in the lecture hall nearby. Humanitarians, stuck in the middle, struggled to keep both stakeholders happy.

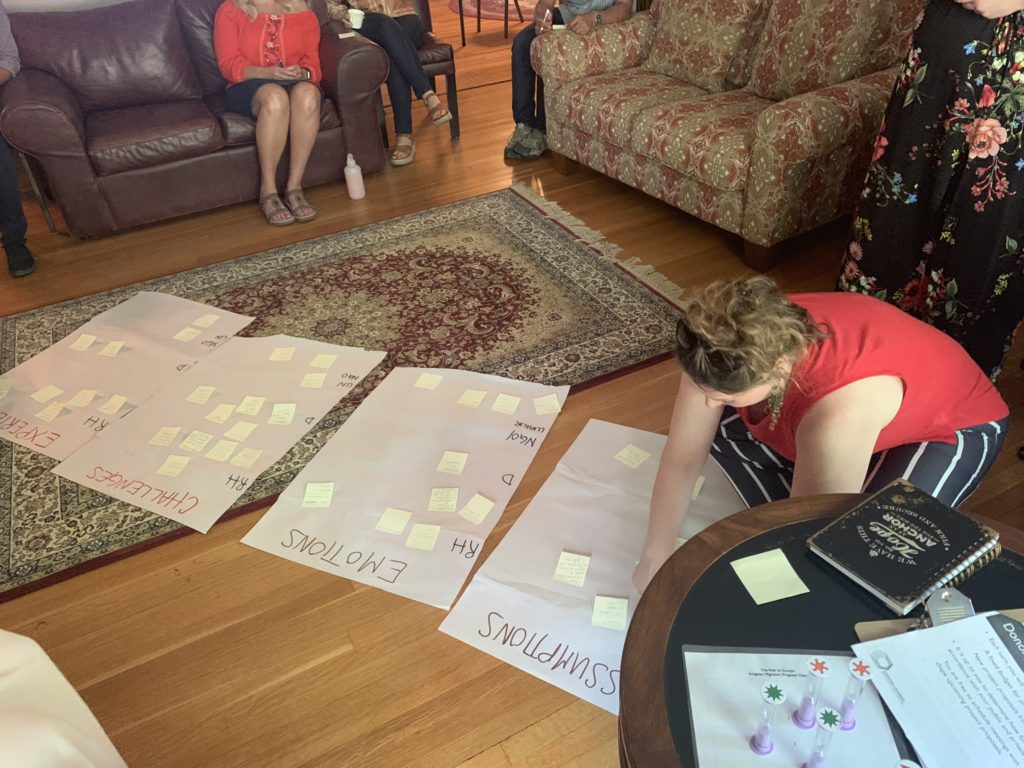

One of the most interesting elements of the simulation (from the standpoint of the lecture team) is how different each experience is. Different groups of people bring different innovations and preconceptions to the exercise; the simulation allows us to explore how consequences of very small changes in approach can ripple into large differences in outcomes. A few exciting simulation take-aways:

- Displaced households were extremely organized with respect to “sharing” taxi rides between neighbourhoods–a new trick that we facilitators hadn’t seen before!

- Several protests very nearly broke out as displaced households claimed repeatedly that humanitarians were “doing nothing”. The humanitarians were most certainly working hard, but inherent challenges in communication between INGOs and households lead to some dramatic miscommunications regarding scheduled interview times.

- Our stalwart donor country representative struggled to work with humanitarian agencies to locate individuals for resettlement, and, when a family finally was put up for resettlement, the donor was quickly able to catch their would-be new citizen up in a crossed story–unable or unwilling to report consistently on how many children were in their family, the nominated individual was unfortunately not seen as sufficiently trustworthy. Why the participant hesitated to report with full honesty, however, did not come out until the debrief.

In the post-simulation debrief, participants were able to learn about one anothers’ perspectives by comparing their “daily actions” with the rest of the group. The group did a magnificent job of highlighting points of confusion and miscommunication, and discussed in detail how different stresses and challenges made them feel. Especially interesting was a conversation around how stressed and overworked humanitarians found the frustration of households to be intimidating. This provoked some serious reflection on the challenge of responding to issues of communication in humanitarian response: if it was this easy to provoke negative response among simulated humanitarian workers, we could imagine how much more charged an interaction must take place with people who are struggling for real.

A final thanks to all participants, speakers, and the Laurentian Leadership Centre team for all contributing to another great event.

…until the next!